Why Adivasis displaced by one of India’s first thermal power plants depend on stolen electricity

Hello,

Hello,

Hello,

Hello,

Hello,

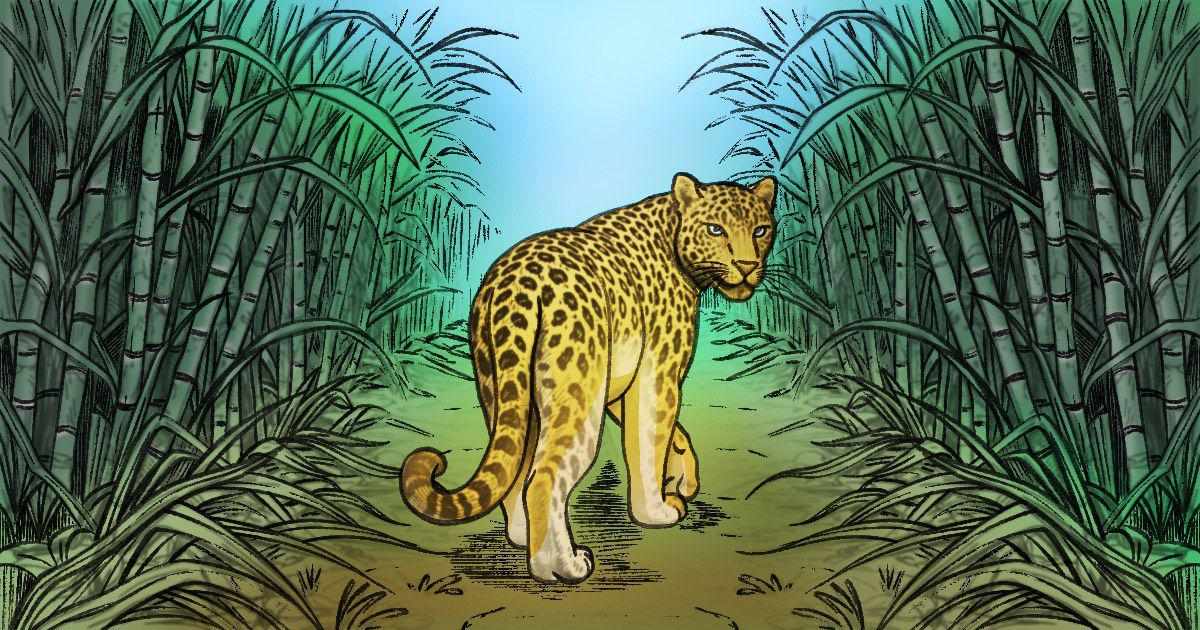

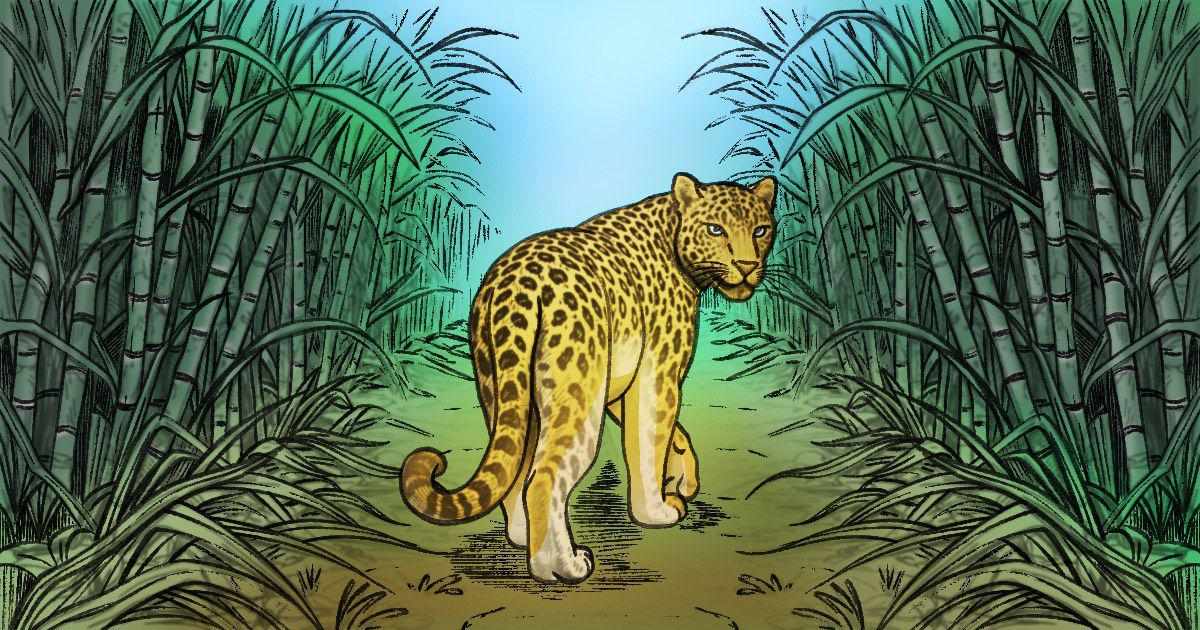

Hello,In 2023, Jharkhand saw 22 murders of people who had been killed on suspicions that they were practicing witchcraft. This was higher than the number of such killings in any other state, and twice the number the state had seen the previous year.Nolina Minj travelled to villages such as Durutoli and Bahvaar Toli, which had seen instances of such attacks in recent times, to understand the extent of the problem. She found that on the ground, most villagers professed a firm belief in the idea that some women practised witchcraft and sought to bring harm to people around them. Meanwhile, families of women who had been attacked, and killed, were left grappling with tragedy, with little support from the government or local communities. Though the state government launched a project in 2020 to tackle the problem, there is little record of what it has accomplished.Worryingly, activists noted that the problem was likely even more serious than the official numbers suggested. “Often, when women are killed deep in rural areas, communities keep quiet and word about the crime doesn’t reach the police,” said Hiramani Deogam, an anti-witch-hunting activist from Chaibasa.You can read the story here.

Hello,

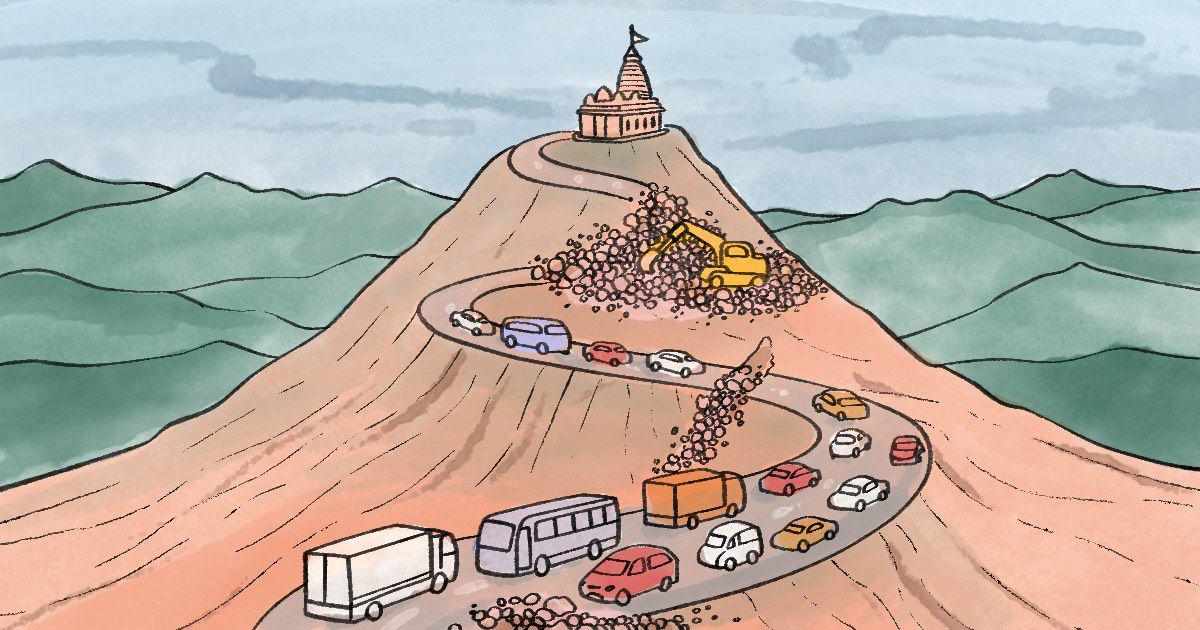

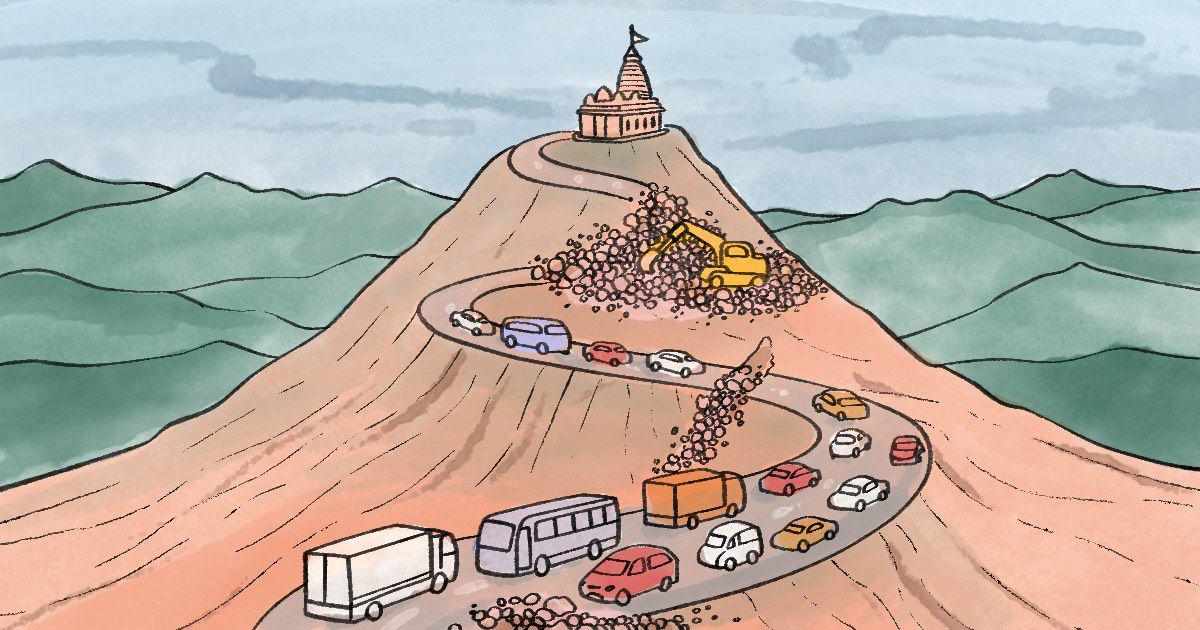

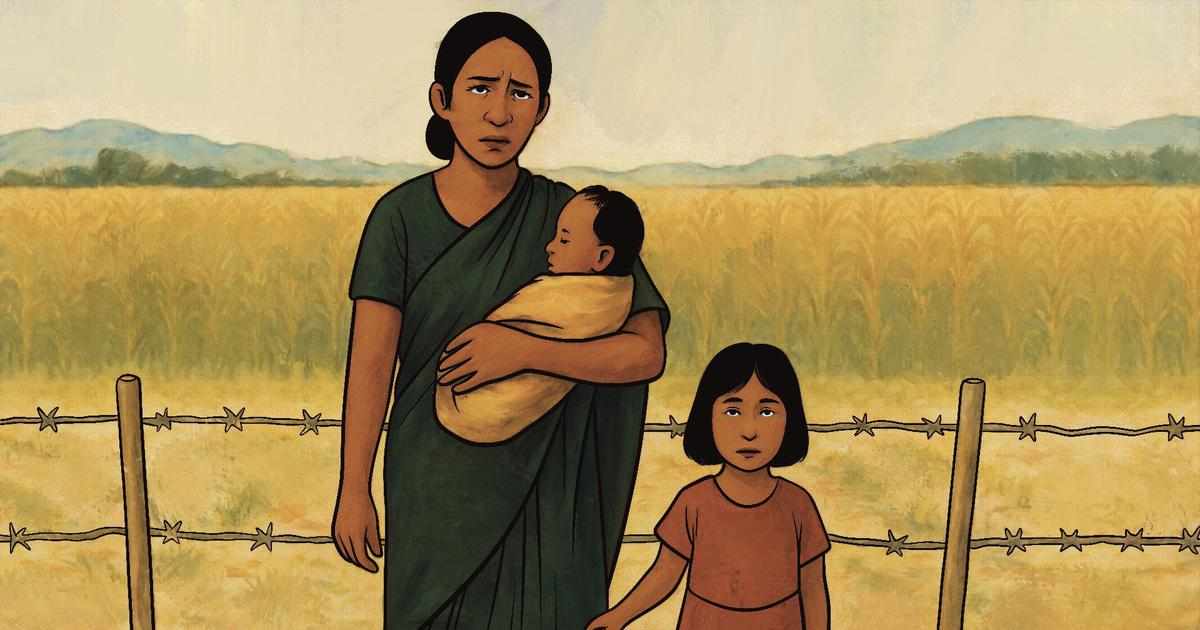

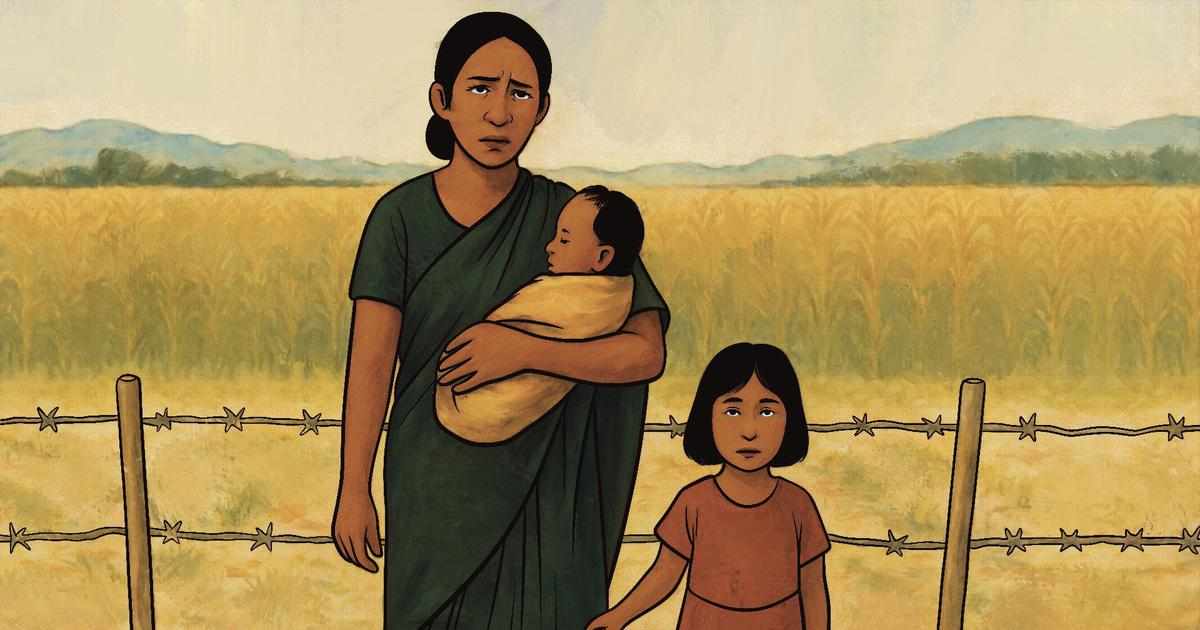

Hello,Two years ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a sweeping scheme that aimed to uplift some of the country's poorest communities. These were the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, many of whom live without basic health and education services, and even necessities such as water and electricity.Modi announced the scheme, named PM-JANMAN, in Jharkhand, a state in which around 4 lakh people belong to these groups. It had a budget of more than Rs 24,000 crore, to be spent towards safe housing, clean drinking water, education, health, telecom connectivity and livelihood opportunities.But when Nolina Minj visited four remote villages in Jharkhand where the scheme was supposedly implemented, she found that work under it had barely made any difference on the ground. In fact, many locals she spoke to had not even heard of it."While I wasn’t expecting top class infrastructure, I presumed that conditions would have at least slightly improved due to the PM JANMAN scheme and other previous interventions," Minj said. "I was in for disappointment." She was particularly struck by how little difference multi-purpose centres that had been constructed under the scheme had made. "The MPC structure at Salgi village was most preposterous as families there still don’t have access to basic facilities like potable water and electricity," she said. "Even in places like Range Tusrukona where the MPC had been running for a while, newborn babies are still dying due to lack of access to proper healthcare."

Hello,In the final months of every year, inevitably, Delhi's air quality plummets to dangerously poor levels and its air pollution frequently makes national headlines.

Hello,

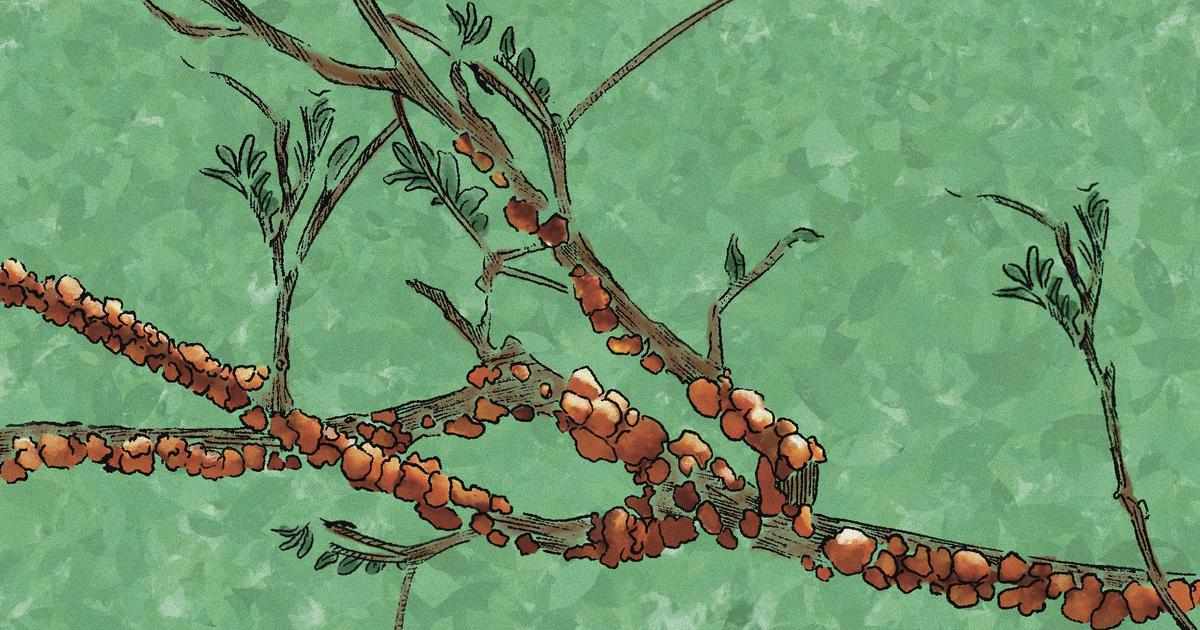

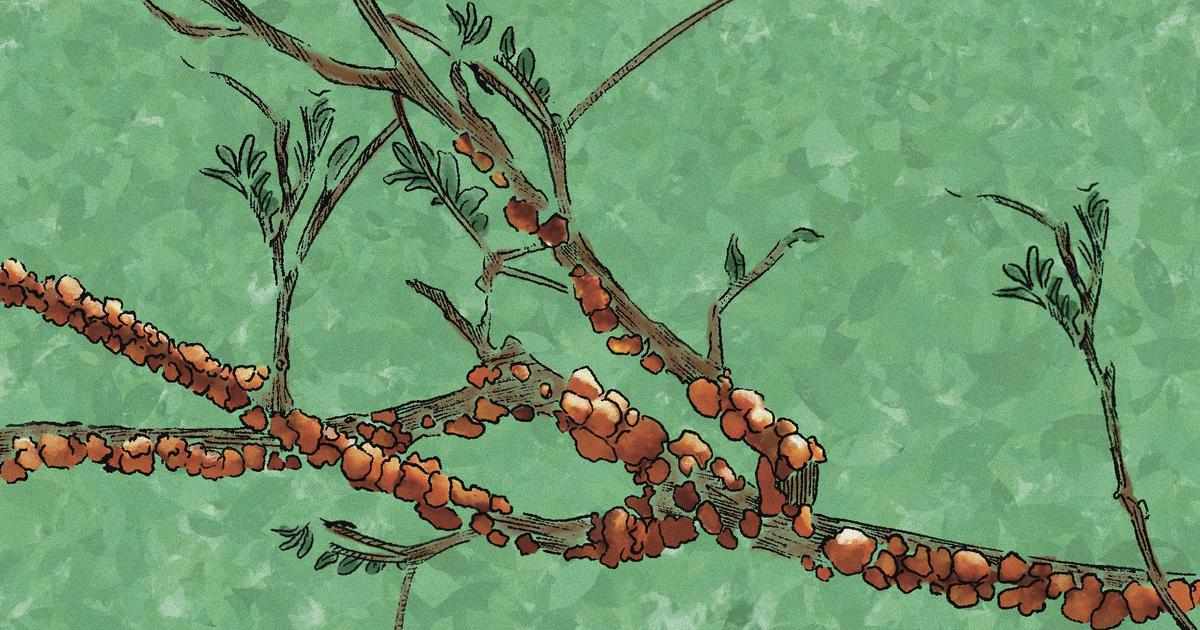

Hello,Every one of us has likely encountered lac in some form or the other. The substance is used in the manufacture of a vast range of products, from cosmetics and jewellery to insulation coating for electrical equipment. It is even used to add polish to products such as fruits and candies.But few of us, perhaps, have thought about where lac comes from. Lac is, in fact, a substance secreted by the Kerria lacca insect, which affixes itself to the branches of host trees like ber and kusum. And, as Nolina Minj found, reporting from Jharkhand, to many in rural India, lac cultivation offers a pathway to a livelihood that is more secure than that of agriculture, and other work."Today our country is the leading producer of quality lac in the world, and over 55% of this production is carried out by small scale Adivasi farmers in Jharkhand," Minj said. "We thus have a sort of monopoly over this natural polymer that's high in demand worldwide."But as experts and cultivators explained, lac production has seen a turbulent history, with output dipping for various reasons at different times, from unscientific cultivation to climate change. Securing the produce against these factors, they noted, would be key to providing cultivators with stable livelihoods."People say there aren't many livelihood options in rural Jharkhand besides agriculture and extractive mining," Minj said. "But then there's lac cultivation – an ecologically sustainable livelihood option if done right, which also holds much economic promise."

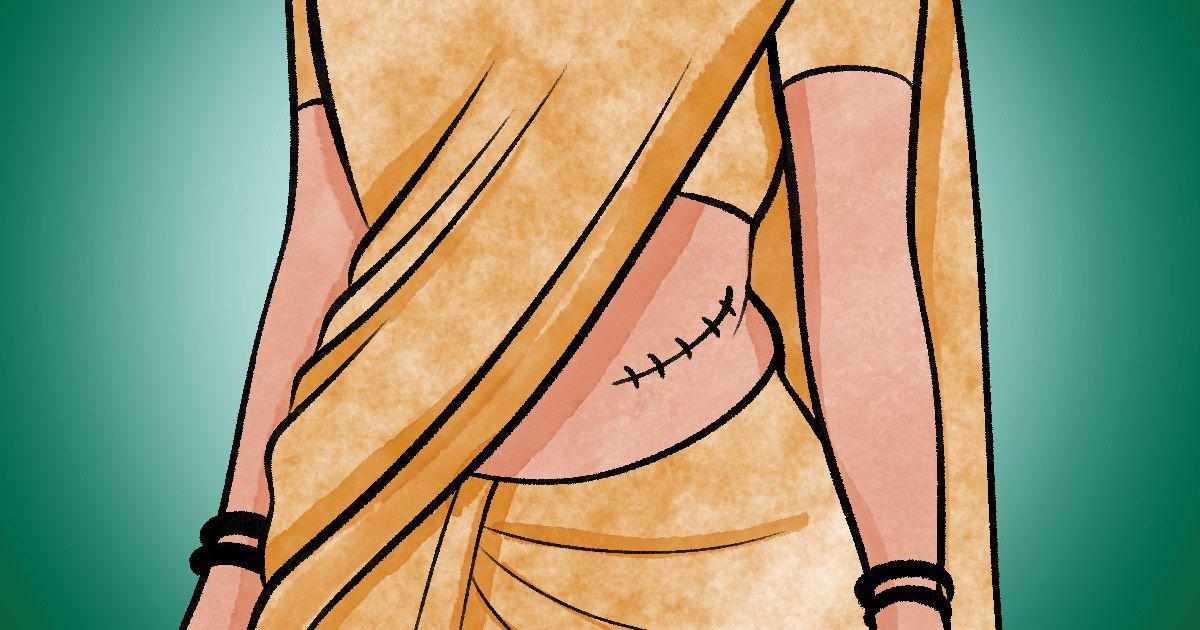

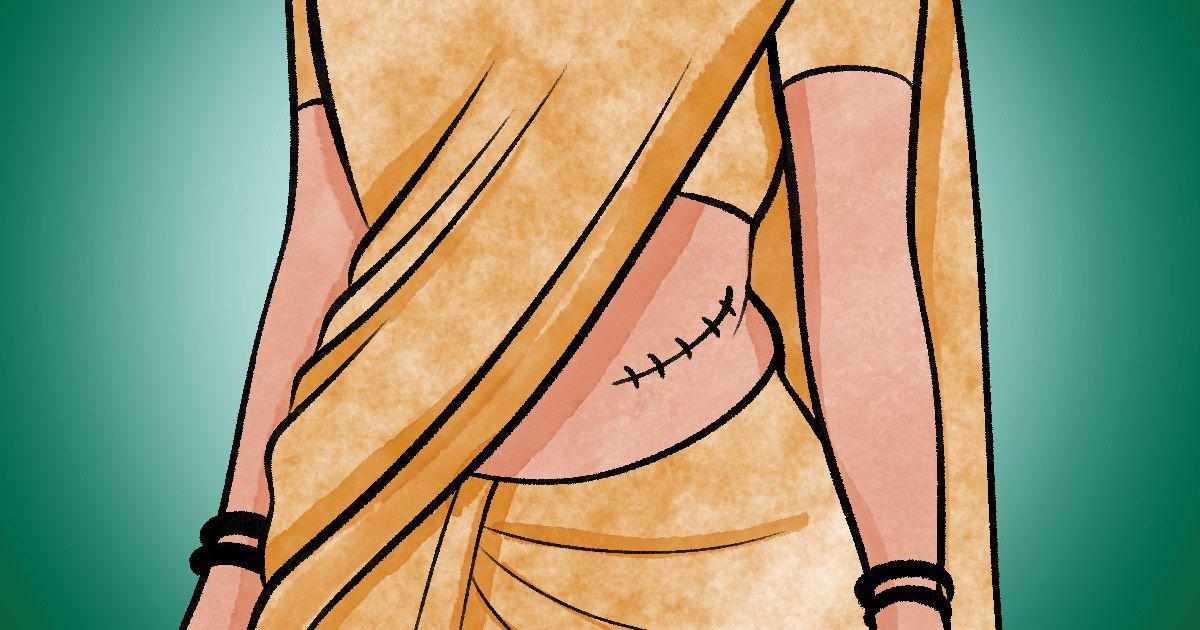

Hello,Among Adivasi communities, land is not seen only as property, especially not as individual property. It is considered a vital part of culture, and under Indian law, the communities' use of land is governed by customary law.In this context, many object to the efforts by some Adivasi women to secure their rights over ancestral lands. They argue that such efforts are in conflict with traditional culture, and that the women should not be granted the rights they seek.But as Nolina Minj found, women note that families often use the idea of customary law to evict women from family lands, and deny them basic resources for their sustenance. Further, they argue that many men have acquired individual rights over land, and that to deny women this security would be a grave injustice."Several Adivasi communities have been steadily losing land to the government, corporations and other private players," Minj said. "There exist genuine anxieties about land loss and the consequent erosion of Adivasi socio-cultural identity."She added, "However, treating Adivasi women’s demand for inheritance as just an avenue for further land grab by outsiders overlooks the immense suffering and dispossession that they are enduring on the ground."

Hello,

Hello,If you are a frequent user of Instagram, there is a good chance that over the past year or so, you have encountered videos by Indian content creators with titles such as “A day in the life of a 21-year-old married woman”.And if you glanced at the views counter, you might have found that the videos had been watched tens or hundreds of thousands of times, or in some cases more than a million times.These videos are in some ways a parallel phenomenon to the trend of “tradwife” videos in the West, by women who glorify marital domesticity, focusing on cooking, homemaking and being good wives. But as experts told Divya Aslesha and Nolina Minj, in the West, this trend represents an embrace of traditional lifestyles, and a rejection of pressures to work and earn a living. In India, however, these content creators are in essence promoting conservative values and lifestyles that are already the norm.“Two of the creators we spoke to used to post content before they were married, but it was only after they started sharing wedding and marriage related content that their followers shot up drastically,” Minj said. “It indicates that the audience and the algorithm likes such content despite their polarised feelings toward the actual content.” She added, “Some of the creators said that hateful comments actually help their engagement. Despite the hate, the creators have learnt to prioritise traction above everything else.”Aslesha noted that while these women were often criticised, “they are also showing us, however inadvertently, the immense contradictions of modern womanhood”. She added, “Social media content is often dismissed as something insignificant, superficial or unworthy of any deeper questions, but this trend says something important about ideas of gender, domesticity, and even how feminist politics and ideas are perceived in Indian society.”You can read the story here.

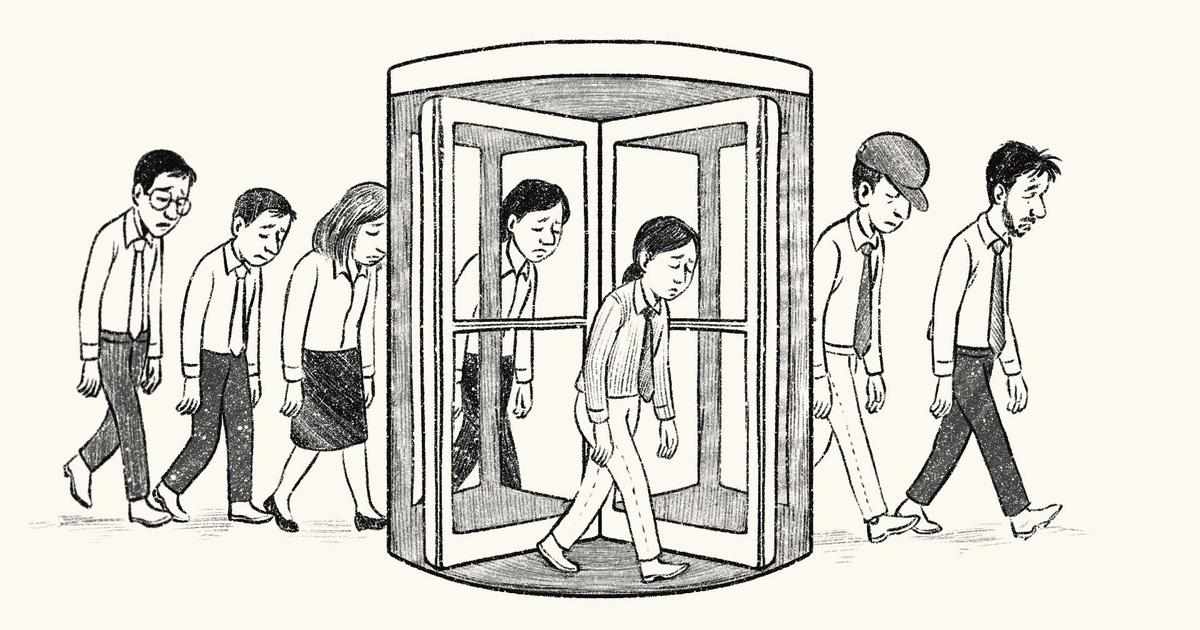

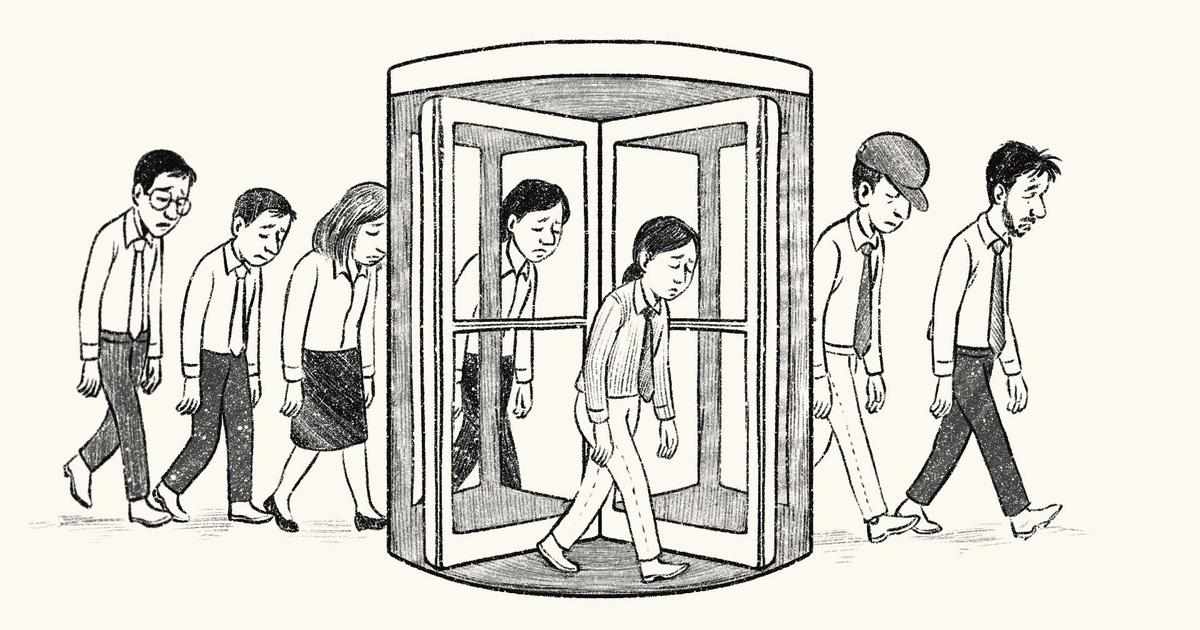

Hello,As Mumbai goes through a redevelopment boom, an egregious practice is becoming commonplace. That is: the barring of domestic workers and delivery persons from residential lifts in apartments, and segregating them into service lifts, or even forcing them to use stairs and roundabout pathways.While building societies offer various justifications for such rules, activists and experts note that they essentially constitute modern forms of casteism. Nolina Minj reported from Mumbai on how these practices lead to distress and inconvenience for workers, who lose immense time and energy as a result. Their protestations and arguments that they are being denied basic rights have thus far largely been ignored.“Dealing with pressing issues like low wages and job insecurity, at first workers didn’t consider separate elevators as a major issue,” Minj said. “However, as they began opening up about their experiences with elevators, the conversations soon revealed how their imposed use felt discriminatory and robbed them of their dignity as human beings.”She added, “I had assumed that within highrise buildings all elevators would be the same, but learning of how service elevators could be made of different materials was quite revealing of the caste-class dynamics in such building societies.”You can read the story here.

Hello,

Hello,Darjeeling tea is perhaps India’s most famous tea, and indeed, one of the world’s most famous teas. Since tea bushes began to be planted in the district in the mid-1800s by British colonisers, the industry has grown to become the region’s economic backbone.But in recent years, it has come under immense strain from a combination of factors, including climate change, competition and sociopolitical strife. Among the government initiatives to help estates survive is a policy that allows them to use a proportion of tea estate land for other purposes.Amidst this turmoil, it is the workers who cultivate the plants who are hardest hit, as Nolina Minj found. Many receive pay that is below minimum wage, often months delayed, and have no rights over their homes on estate lands.“As tea estate owners and workers explained, Darjeeling tea is considered a national pride, often gifted to foreign dignitaries by Indian political leaders,” Minj said. “The crisis in the Darjeeling tea industry is deeply entwined with the tea estate workers’ crisis. Darjeeling tea is produced because of them and the future seems bleak if both the tea industry and the workers’ conditions are not improved.”You can read the story here.

Hello,Residents of Indian cities now more or less expect that they will flood within hours of monsoon rains every year. Many believe that the cities are simply not designed to handle the level of rain they receive.But in fact, some are equipped with fairly robust stormwater drain systems, as Vaishnavi Rathore found, looking at the example of Delhi. It was, primarily, poor management of this system and unregulated construction over it that left the drains clogged and useless in many parts of the city. In Delhi, the failure to resolve this problem was particularly stark given that some years ago, the government commissioned a study on it by IIT Delhi, only to shelve its analysis and recommendations.

Hello,

Hello,It is unlikely that you have very recently given much thought to snakes, or the risk of snakebites. It is a danger that few among the relatively well-heeled in Indian society ever encounter.

Hello,